Something to Think About

Point of View, AI and Cognition, 2025

Much of today’s digital design is governed by a principle of frictionlessness. Interfaces are made intuitive, interactions seamless, and outputs immediate. While this makes sense in fields like logistics, it becomes problematic when applied to creation. In creative or conceptual work, resistance is the terrain, not the obstacle.

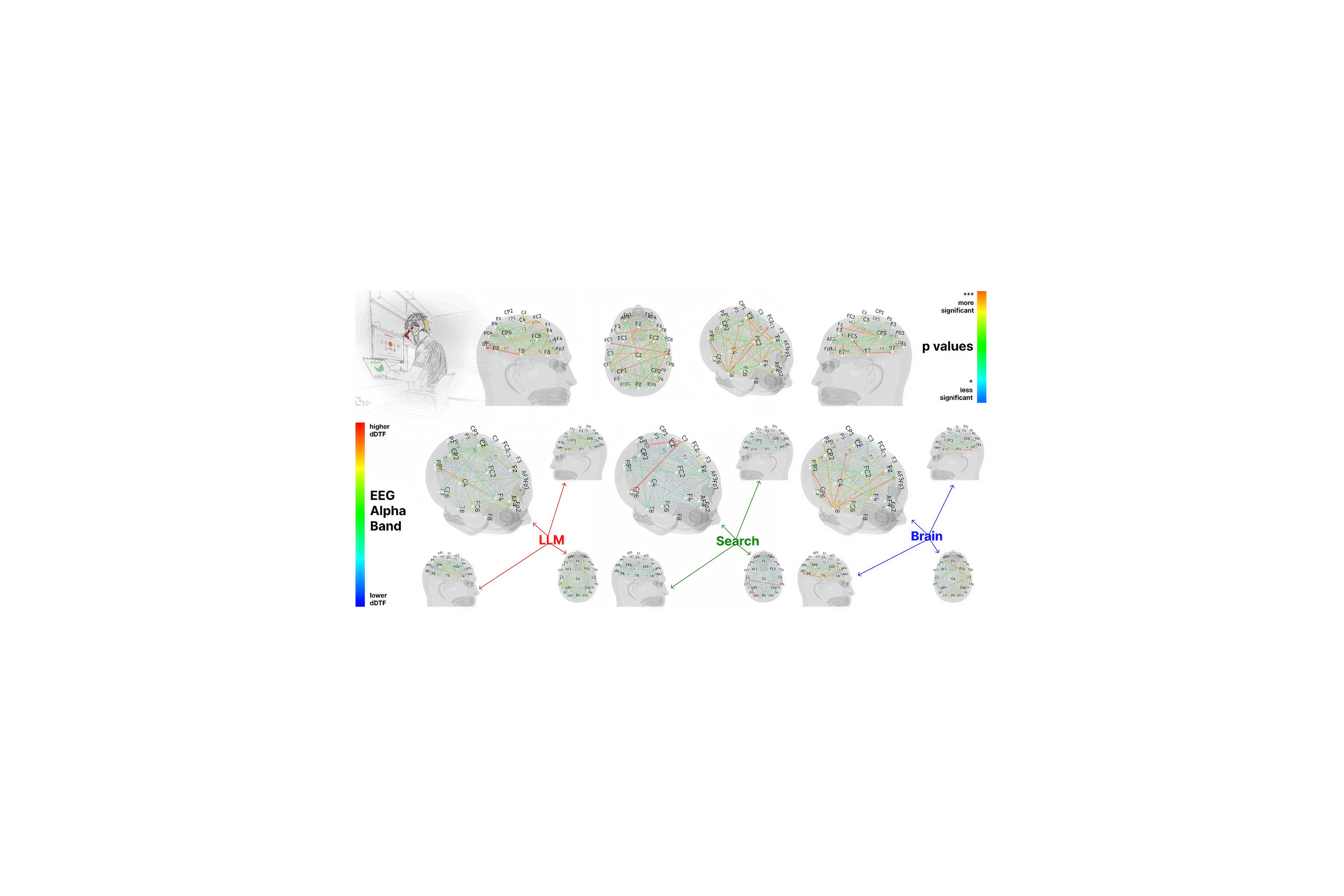

Recent studies give form to this concern. At MIT, students using generative AI to compose essays showed significantly lower brain activity, particularly in areas related to working memory and original thinking. Many could not recall the contents of what they had produced, nor did they feel connected to the work. A similar study at Cornell found that AI-generated writing pushed users toward cultural convergence. Indian and American participants, when assisted by AI, tended to adopt similar rhetorical habits, defaulting to Anglophone norms and smoothing over regional inflections. What emerged was not fluency, but sameness.

Sociologist Richard Sennett warned about this long before generative systems entered the picture. “All skills,” he writes in The Craftsman, “even the more abstract, begin as bodily practices.” Sennett’s point is not nostalgic, but neurological: without some form of struggle, bodily, material, or conceptual, the mind does not develop depth. The more friction is eliminated from a task, the less opportunity there is for embodied cognition to take root.

Michael Polanyi captured this with his notion of tacit knowledge: a form of understanding gained not through rules or data, but through direct experience. The feel of wood beneath the hand, the balance of a spinning pot, the tuning of a phrase in real time, these are all ways of knowing that cannot be outsourced or scripted. They emerge only through repeated, situated interaction with the material at hand.

Working to remember

From daubing stories on cave walls, to writing journals or reciting thoughts into dictaphones, as our knowledge has grown so have our means to contain it. What one might once have learned by rote, is now captured and held handily in one or more of our devices, always available for recall at a swipe, click or verbal prompting.

This incremental reduction of effort is not new, nor is it entirely unwelcome, except that the old journey to remember not only served to exercise the memory but often to enrich what is being remembered.

When we grasp at a memory, we might try to lasso it by remembering its context, its colour, the starting letter, the timeframe; slowly homing in on it as we fill in our mental gaps. Or we may retrace our steps in the hope of stumbling on a trigger that unveils where that poltergeist moved the car keys, again. But the more brilliantly our tech joins the disparate strands of our calendar entries, search histories, photo reels and playlists for us, the less we have to cultivate the signposts that lead us back to stories or songs or facts, or even the mechanisms needed to describe them so that someone else might remember the way.

Bull rock art Neolitihc

Resistance as a teacher

The value of embodied learning is particularly visible in music. Playing an instrument involves an ongoing process of calibration: fingers adjust pressure, the ear listens for pitch, timing is refined in the moment. Research from MIT (2022) confirms that musical training activates both hemispheres of the brain, analytical and creative, linguistic and spatial. Memory encoded through music is tagged across multiple sensory modalities, leading to stronger and more resilient recall.

The act of learning music integrates many cognitive functions at once, creating a kind of cross-training for the mind. This effort is not a precursor to understanding, it is what allows understanding to take form in the first place, lodging memory in our very fingers. A learned dexterity that makes the complex appear easy.

A violin, for example, is not a machine that executes instructions. It is an instrument that pushes back, requiring the musician to respond, revise, and remain present.

A study from Rosebud O. Roberts, M.B., Ch.B. at the Mayo Clinic found that people who engaged in hands-on craft activities during middle and late life had a 45% lower risk of cognitive decline. These “cognitively stimulating activities,” which included everything from quilting to woodworking, appeared to build what psychologists call cognitive reserve, a buffer against neurological aging.

In weaving, another example, we find not only tactile pleasure but complex spatial reasoning. A study from the University of Hertfordshire’s Everyday Lives in War project documented how stroke patients who practiced basket weaving saw improvements in spatial awareness and fine motor coordination. The physical structure of the work, interlacing tension, geometry, and rhythm, became a scaffold for neurological repair for people affected by dementia.

Even the most skilled performers or craftspeople must remain attentive. But this attentiveness is not a sign of inefficiency, it is where meaning is made, every artist’s rendering, a unique record of their own relationship to their material.

Complexity as a catalyst

When the tools we use are intuitive, our mediums stable and our knowledge centralised, our output becomes pleasantly reliable and the opportunities for human error vastly reduced. In a creative context, however, contemporary tech-enabled ease may often prevent the very marks of friction that make things unique. Wabi-sabi has long celebrated the imperfections that make something recognisably human, while in craft, the traces of individual technique are what add value, not how much something is indistinguishable from its batch.

Even clarity sometimes comes at the cost of creativity, as the potential for points of interpretation and divergence that typically thrive in the murky recesses of ambiguity are banished by terse, optimised tags. Children also develop vital skills of abstraction when their imaginations outstrip their resources. Without a literal orchestra at their disposal, they turn a tennis racket into a guitar, a brush into a microphone, a pot becomes a drum.

Some inventors are beginning to develop tools that restore this imaginative friction. Our friends at Tame, describe their AI tool as an instrument for lateral reasoning: an OS that is curious and reflective, that challenges your inquiry and helps you go deeper in your creative process by confronting your idea with the right questions. Even as you login to your personalized OS, you are greeted by a prompt that can derail your train of thought, or add flavor to an idea you are incubating.

Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task, MIT